Equine Metabolic Syndrome:

Diagnosis

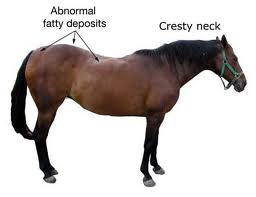

Diagnosis of Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS) is primarily based on clinical signs and body type. The classic EMS horse has a heavy, cresty neck, and abnormal fat distribution with excess fat accumulated at the tail base and in the sheath or mammary gland region. While we tend to think of metabolic syndrome horses as overweight, this is not always the case.

The use of insulin testing to diagnose and monitor response to treatment is widely discussed, but in practice is very difficult to interpret accurately. Here's the problem: most horses first present to the veterinarian with EMS during a bout of clinical laminitis. Once in pain, the horse enters a stress state, which is characterized metabolically by an increase in circulating cortisol levels. When we are in stress, our bodies respond by preparing to fight or run - it is the natural survival mechanism which keeps animals alive in the wild. To fight or run we need energy - one of the major actions of cortisol is to raise blood sugar. By now you have learned what high blood sugar causes: that's right: increased insulin! So the EMS horse with active foot pain typically has an elevated insulin and blood sugar. But so do many NON EMS horses with laminitis. It is impossible to interpret the significance changes in insulin in a horse that is experiencing activie laminitis. So, even though insulin and glucose frequently are measured in such horses to get a baseline idea of their status, it is critical to come back when the laminitis has been managed successfully to obtain a fasting insulin level and even perform a glucose tolerance test when the horse is not physiologically stressed.

Ideally, if you have a horse with the fat distribution suggestive of EMS, you should ask your veterinarian to perform a fasting insulin level, or a simple oral glucose tolerance test, BEFORE your horse ever develops laminitis. As horse owners become more educated about EMS, hopefully this practice will become more common. If you are able to detect insulin resistance in your horse before clinical signs of the problem are present, then by careful dietary management you may never have to experience the heartbreak of laminitis.

Please spread this information to all your horse owning friends, especially if you see a horse with the typical EMS body type. Early diagnosis and careful dietary management is the key to preventing laminitis in EMS horses.

In the early stages of EMS, affected horses may have normal resting blood insulin. These patients may benefit from a glucose tolerance test. This can be performed in a hospital setting, where a glucose load is administered intravenously, followed by a dose of insulin, and the horse's blood glucose is measured serially over time. This test is useful, but is expensive and labor intensive, and should be conducted in a hospital because of the risk of hypoglycemia following insulin administration.

In a field setting, there are two levels of insulin testing that can be performed safely and efficiently. The first is a simple fasting insulin level, where blood is drawn 10-12 hours after a hay meal the night before. The second is a modified glucose tolerance test. The horse is fed a hay meal the night before, then in the morning the owner gives a dose of karo syrup (15 ml/100 kg BW - your veterinarian will calculate this and tell you how much to give). Your veterinarian comes 60 - 90 minutes later and draws blood for insulin and glucose.

In summary, remember that the typical EMS horse, pain free and at rest, has a normal blood glucose and an elevated insulin. Early diagnosis, before the onset of laminitis, is our goal. Spread the word, and help prevent laminitis.

I believe that education is the key to evolution. I believe that animals are the key to compassion. I believe the learning never stops.

PO BOX 60730

RENO NV 89506

EMERGENCY (775) 742-2823 OFFICE (775) 969-3495

FAX (775) 969-3923